Infant CPR: What to Do When Baby Is Choking

Babies have a long, adorable list of skills to learn: how to crawl, how to stand, how to turn those babblings into fluent conversation, how not to drop a spoon on the floor for the fifth (or sixth!) time. Safely chewing and swallowing are on that list too. While infants are born ready to eat, they’re not totally primed to avoid choking. Here’s what you need to know about preventing baby from choking and how to perform infant CPR in the event of a worst-case scenario.

“Infants have a relatively limited repertoire of things they can do for themselves,” says Joan E. Shook, MD, MBA, chief of pediatric emergency medicine at Texas Children’s Hospital and professor of pediatrics and emergency medicine at Baylor College of Medicine. “From birth to about 4 months, their choking hazards typically are the things you’re putting in their mouth.” Young babies can choke easily because they haven’t yet developed the ability to handle a variety of textures, explains Whitney Casares, MD, MPH, FAAP, a Portland, Oregon-based pediatrician, founder of Modern Mommy Doc and author of Doing It All: Stop Over-Functioning, and Become the Mom and Person You’re Meant to Be. “Difficulty handling breast milk, formula or saliva are common causes of choking in young infants, but babies can also choke on mucus from nasal secretions that drip down the back of their throats during a respiratory illness, for example,” Casares explains.

Once baby begins crawling the game changes significantly, since babies use their mouths to explore their environment. “When you have an older child putting foreign objects in their mouth, that can be a completely different kind of choking event,” Shook says. The most common causes of an older baby choking include small items that block the airway (think: toys, buttons, chunks of solid food or coins), as well as behaviors like eating too much in one bite. “Babies don’t have the cognitive ability to think, ‘If I put this one Cheerio in my mouth, I should swallow it before I take the next 50,’” Shook says. “They’ll cram their little mouths full of whatever, and then they don’t know how to navigate it.” That’s why it’s so important for parents to closely watch their little ones and keep small objects out of their hands, says Casares.

Before you even get to this worst-case scenario, the smartest thing you can do is take a class on baby choking and infant CPR. “In the heat of the moment, it’s hard to know how to do it correctly,” Shook says. “Although 911 can walk you through it, if you’ve never done it, it’s very difficult.” To find a class near you, go to the American Red Cross website and enter your zip code. You’ll see options for in-person training (Shook’s preferred choice) as well as online classes.

Here’s a run-through of how to tell if baby is choking, and what to do if baby chokes, according to our experts and the American Red Cross.

Gagging vs. choking baby

It’s important to tell whether baby is gagging or choking. When baby is choking, they may be completely silent and turn blue or red in the face, says Casares. “They may appear panicked, or they may wheeze. If they’re old enough, they may also hold their neck.” On the other hand, when baby is gagging, they’re generally very loud, she says. “They may retch, cough or cry when gagging.”

When baby’s gagging, the best thing to do is not intervene and let baby cough it out—it’s the best way to dislodge a partial blockage. Don’t perform a finger sweep (sticking your finger in baby’s mouth to try to grab whatever’s in there) if you can’t see the object because it could push the object further down baby’s throat, as per Mayo Clinic.

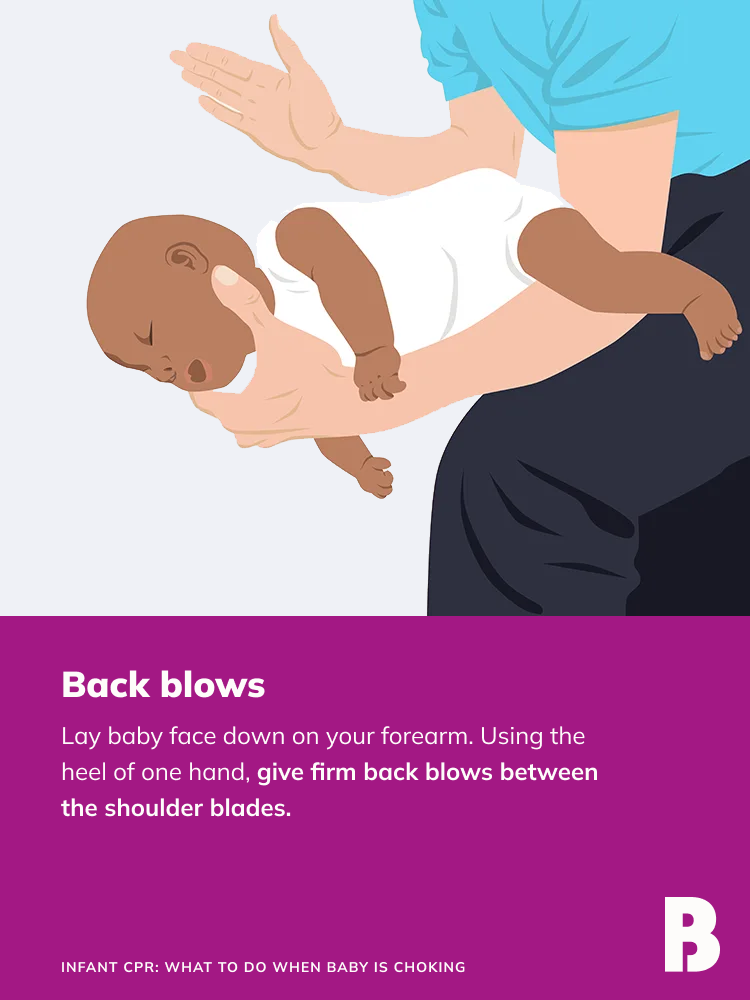

Back blows for choking infant

If baby can’t successfully cough up the object, or if baby has a complete blockage (meaning no air is getting in or out of baby’s lungs), you’ll need to take action. Ask someone to call 911 and then try to dislodge the object with back blows and chest thrusts—steps designed to remove the object without harming baby’s body. (The Heimlich maneuver, while safe on adults, could damage organs in baby’s delicate torso, so you don’t want to attempt that.) If you’re alone with baby, first deliver back blows and chest thrusts for two minutes, then call 911 and follow their directions for care.

• To perform back blows: Lay baby face-down on your forearm with their head supported by your hand and their chest higher than their head. Using the heel of one hand, give five firm back blows between baby’s shoulder blades.

• To perform chest thrusts: Lay baby face-up on your forearm with their skull supported by your hand and their head lower than their chest. Place two or three fingers in the center of their chest just below the nipple line, and compress the breastbone about 1.5 inches. That’s one chest thrust; perform five.

Alternate between doing five back blows and five chest thrusts, rolling baby from back to front until the object is ejected or baby forcefully coughs, cries or breathes. If baby becomes unconscious with the object still lodged in the throat, carefully lower them onto a flat, firm surface and begin giving infant CPR.

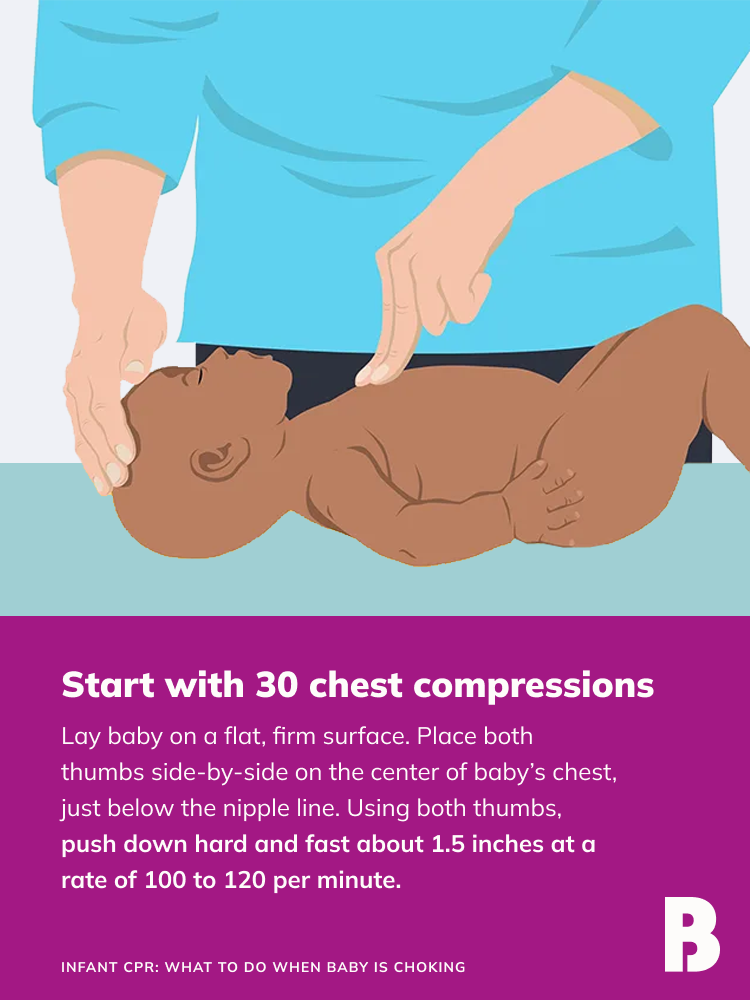

You should first check if baby is unconscious by shouting their name, as per the American Red Cross. If baby doesn’t respond, you can tap the bottom of their foot and shout again. Check for breathing, life-threatening bleeding and any other obvious life-threatening condition. If baby doesn’t respond and is not breathing or is only gasping, call 911 or tell someone to do so. Perform infant CPR by following these steps:

1. Start with 30 chest compressions. Lay baby on a flat, firm surface (like the floor). Place both thumbs side-by-side on the center of baby’s chest, just below the nipple line. Use the other fingers to encircle baby’s chest toward the back, providing support. Using both thumbs simultaneously, push down hard and fast about 1.5 inches at a rate of 100 to 120 per minute. Allow the chest to return to its normal position after each compression.

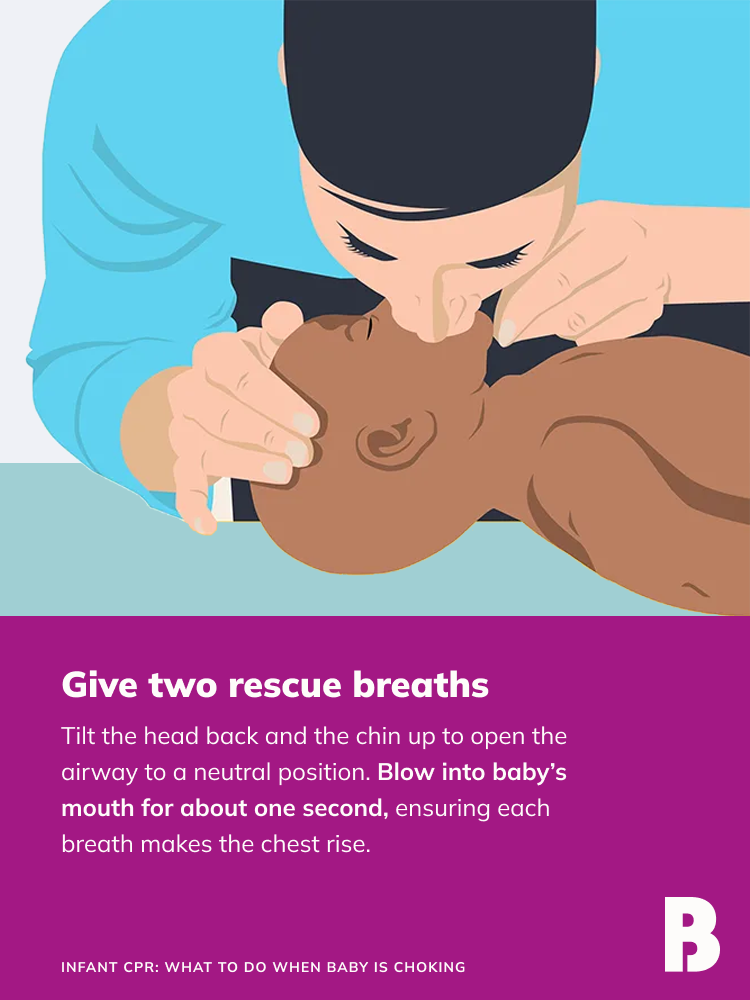

2. Give two rescue breaths. Tilt the head back and the chin up to open the airway to a neutral position. Blow into baby’s mouth for about one second, ensuring each breath makes the chest rise. Allow the air to exit before giving the next breath. If the first breath doesn’t cause the chest to rise, retilt the head and ensure a proper seal before giving the second breath. If the second breath doesn’t make baby’s chest rise, there might be an object blocking the airway.

3. Continue giving sets of 30 chest compressions and two breaths until you notice an obvious sign of life or a trained responder is available to take over.

Lastly, any and all of baby’s caregivers (nanny, grandparents and so on) should know how to perform infant CPR in case of an infant choking emergency. The American Red Cross offers a First Aid mobile app, free for both iOS and Android users, that gives step-by-step instructions for how to perform back blows, chest thrusts and infant CPR (as well as CPR for children and adults.) These measures could very well save baby’s life.

There are many steps parents can take to prevent choking in babies. The first step is to keep small toys, such as marbles, deflated balloons and bouncy balls, as well as tiny household items, like button batteries, marker caps and loose change, out of baby’s reach. “If an object can fit through a toilet-paper tube, an infant can put it in his mouth and choke on it,” Shook says.

Keeping a close eye on baby during mealtime is also a must. Use these guidelines to help prevent baby choking while eating:

-

Introduce solid foods when baby is ready (typically around 4 to 6 months). Baby will need to be able to hold their neck steady, draw in their lower lip when you pull out a spoon and swallow food rather than pushing it out onto the chin before getting their first taste of solid food.

-

Only offer foods that are developmentally appropriate. “To prevent choking when introducing foods, start with small amounts of food at a time,” says Casares. “Only give food that babies can smash easily in their hands and mouths. When offering solid foods to babies, they should be soft and not hard.” If you’re doing baby-led weaning, make sure to follow the appropriate guidelines for cutting and serving food.

-

Avoid high-risk foods such as hot dogs, nuts, raw veggies, hard candy, seeds, popcorn and grapes. And if it’s soft and round, like a grape or hot dog, it needs to be sliced into very small pieces before baby gets their chubby fingers on it.

While no one wants to think about these scary moments, it’s important to be armed with information in case a baby choking incident arises. Performing back blows, chest thrusts and infant CPR are all key skills. But one of the most crucial things you can do is learn how to prevent choking in babies in the first place—it will go a long way to put your mind at ease.

Please note: The Bump and the materials and information it contains are not intended to, and do not constitute, medical or other health advice or diagnosis and should not be used as such. You should always consult with a qualified physician or health professional about your specific circumstances.

Plus, more from The Bump:

Whitney Casares, MD, MPH, FAAP, is a Portland, Oregon-based pediatrician, founder of Modern Mommy Doc and author of the forthcoming book Doing It All: Stop Over-Functioning, and Become the Mom and Person You’re Meant to Be.

Joan E. Shook, MD, MBA, is the chief of pediatric emergency medicine at Texas Children’s Hospital and professor of pediatrics and emergency medicine at Baylor College of Medicine. She received her medical degree from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine.

Mayo Clinic, Choking: First Aid, October 2022

American Red Cross, Child and Baby CPR

Learn how we ensure the accuracy of our content through our editorial and medical review process.

Navigate forward to interact with the calendar and select a date. Press the question mark key to get the keyboard shortcuts for changing dates.