Baby Is Coming: What to Know About Cervical Dilation

It’s no secret that your body will go through some major changes during pregnancy in order to ready itself for labor and delivery. Your vaginal discharge may increase and get thicker, and your bump may drop as baby settles deeper into your pelvis. But one transition that isn’t visibly obvious to you is cervical dilation. A few weeks before baby’s anticipated arrival, your doctor or midwife may start checking to see if your cervix has started opening at all (it’s how baby’s head is going to fit through the birth canal!). Suffice it to say, it’ll go from completely closed to wide open. But what exactly does cervical dilation entail, how important is it to labor and delivery and is it possible to speed this process along? Here, we share everything you need to know about cervix dilation in pregnancy and labor.

Cervical dilation is a natural and biological part of labor and childbirth, says Meleen Chuang, MD, an ob-gyn and medical director of women’s health at the Family Health Centers at NYU Langone. During the laboring process, you’ll hear a lot about cervical dilation and effacement, both of which refer to changes that happen in the cervix as the body prepares to deliver baby. Toward the end of pregnancy, as labor approaches, the cervix must thin (effacement) and open (dilation) to accommodate baby during delivery.

Cervical dilation is measured in centimeters, with 0 centimeters being completely closed and 10 centimeters (the approximate width of a newborn’s head) being fully dilated. You must have a fully dilated cervix in order to start pushing baby through the birth canal.

When do you start dilating in the third trimester? Per the American Pregnancy Association (APA), both cervical dilation and effacement start once baby drops down into the pelvis. This puts pressure on the cervix and causes the body to prepare for labor. This all occurs during the first stage of labor (also known as early labor), and it’s one of the first signs that baby’s coming soon—but maybe not as soon as you might think.

So much emphasis is put on cervical dilation during the labor process, but you can actually start dilating weeks before your body is ready to push baby out, notes the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). In fact, some women may experience cervical dilation without realizing it. So if your doctor says you’re 1 centimeter dilated at your 37-week checkup, don’t assume that baby’s arriving pronto. “I’ve seen patients become dilated about 3 or 4 centimeters without active labor,” says Nicole Williams, MD, an ob-gyn in Chicago, Illinois. “They’re usually in their late third trimesters.”

On the flip side, it’s also normal for the cervix not to be dilated at all before labor. So don’t worry if you’re 40 weeks along and still measuring at 0 centimeters; your body could still be preparing for labor and delivery in other ways. Cervical dilation is just one piece of the puzzle in the laboring process. “Dilation alone doesn’t really mean much until you’re in labor,” says Denae Ellson, CNM, a certified nurse midwife in Edina, Minnesota. “When we do a cervical check, we’re looking at more than dilation. We’re looking at how soft it is, its position and how open it is.” (More on that below.)

Once the body moves into active labor, cervical dilation will happen more predictably, “about 2 centimeters every 2 hours,” Chuang says.

Cervical dilation in preterm labor

Having a dilated cervix near the end of pregnancy is usually no cause for concern—your body is just progressing toward the finish line. However, if your cervix starts to dilate too early, it could be a sign of preterm labor, which could require further evaluation and even hospitalization, according to Williams. There are a variety of reasons the body may go into preterm labor, but if it’s specifically a cervical issue, it may be caught on an ultrasound before any dilation actually begins. Ellson explains that sometimes “the cervix just isn’t capable of staying closed because of the weight of the pregnancy,” which can cause it to start dilating as early as the second trimester. The good news is that this is rare, and it’s often identified early enough that you and your doctor can develop a plan.

At its onset, most women won’t notice any physical cervical dilation symptoms. But one big tip-off that dilation has started? You might lose your mucus plug, Chuang says. This is a clump of thick mucus that blocks the opening of the uterus during pregnancy to protect baby from bacteria. As the cervix begins to open, the mucus plug dislodges and comes out like discharge. Along with this, you may also experience the “bloody show”—which isn’t much different from the mucus plug—and occurs when a blood-tinged mucus begins to come out of the vaginal canal as a result of cervical changes.

Once things start heating up and labor is officially underway, you’ll begin to notice more signs of dilation. What does dilation feel like? You won’t be able to feel the cervix opening, Ellson says, but what you will feel are the uterine contractions that work to stretch the cervix open. “As the uterus contracts, it pulls the cervix up slowly and steadily, which results in it opening wider,” she says. Just how painful these contractions are varies from woman to woman. Chuang notes other signs of cervical dilation can include cramping and pelvic pressure.

If you have an uncomplicated pregnancy, your doctor or midwife will typically start routinely checking for dilation after the 39-week mark (but they may start checking earlier if you’re having any symptoms of possible early labor, such as contractions). You’ll also be examined throughout your labor experience to see how things are progressing. You can expect to be checked by hand; practitioners are all trained to measure the opening of your cervix with their fingers, Williams explains.

To check the cervix, Ellson says that “providers place two gloved, lubricated fingers into the vagina and reach up until their fingers can touch the cervix; then with the two fingers we measure how wide the opening is.” These exams shouldn’t be painful, but they may be a bit uncomfortable.

Checking cervical dilation at home

Since this is a manual exam, it’s technically something that can be done at home. You may be wondering how to check cervix dilation and effacement in a safe and useful way yourself. However, checking cervical dilation at home comes with the risk of spreading bacteria to the area, which can cause infections and complications. What’s more, unless you have medical training, it’s hard to know exactly what you’re feeling for. It’s best to talk to your doctor or midwife before taking matters into your own hands, so to speak—and most experts will say it’s best to leave this to the professionals. “Self-checking can lead to incorrect measurements and potential complications such as cervical bleeding and increase the risk of infection to the baby,” Chuang says.

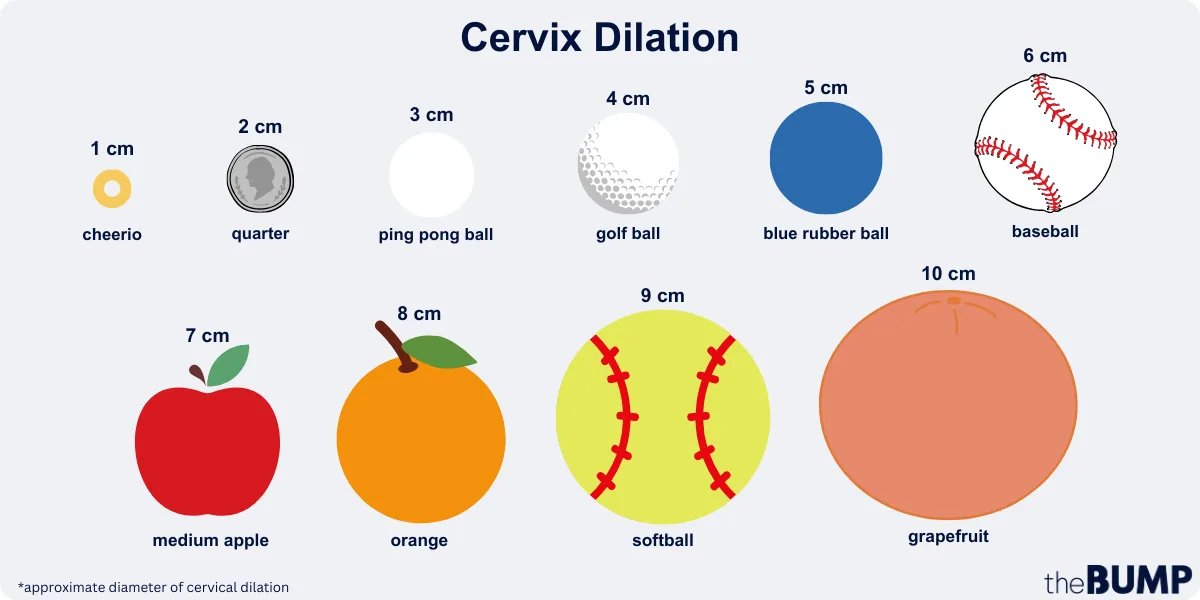

To help you understand just how dilated you’ll become from 1 to 10 centimeters, we asked the experts for a breakdown using everyday objects. Below, Chuang offers a visual understanding of cervical dilation and a handy cervix dilation chart:

- 1 cm: Approximately the diameter of a Cheerio

- 2 cm: Approximate the diameter of a quarter

- 3 cm: Approximately the diameter of a ping-pong ball

- 4 cm: Approximately the diameter of a golf ball

- 5 cm: Approximately the diameter of a blue rubber ball

- 6 cm: Approximately the diameter of a baseball

- 7 cm: Approximately the diameter of a medium apple

- 8 cm: Approximately the diameter of an orange

- 9 cm: Approximately the diameter of a softball

- 10 cm: Approximately the diameter of a grapefruit

We get it—you’re eager to get this show on the road. Unfortunately, there isn’t a whole lot you can do on your own to make your cervix dilate faster. “The process is controlled by hormonal and muscular factors, and it progresses at its own pace,” Chuang says. What’s more, she notes, “There’s no set duration for how long you can stay dilated at a specific measurement.”

Still, while there’s no sure-fire way to expedite labor, Ellson says there are a few steps you can take “to help tip the scales” and nudge things along. In order for your cervix to dilate, you need strong uterine contractions. Ellson explains that the best way to get these going is by supporting the natural release of oxytocin in the body. Here are some ways to do this:

-

Move your body. A study found that women who participated in regular water exercise throughout pregnancy experienced shorter first and second stages of labor than those who were not active in the same way. Light exercise during early labor can also help. Ellson explains that movement can boost oxytocin, which will lead to stronger contractions and quicker cervical dilation. In other words, as those regular contractions start to kick into gear, consider doing some low-intensity exercises to dilate the cervix faster, or just go for a walk while you still can.

-

Try having sex. While there’s no solid consensus, some research and ample anecdotal evidence have associated sex around the time of your due date with cervical changes that can ultimately kick labor into gear. The prostaglandins in semen can potentially help with effacement, while a release of oxytocin from an orgasm can get cervical dilation-causing contractions going. Having sex late in pregnancy is generally considered safe; however, some moms-to-be with certain risk factors may have to abstain, so check with your doctor or midwife to get the green light first.

-

Nipple stimulation. If you’re past your due date and get approval from your provider, Ellson says you can help your cervix get ready for labor and trigger your body’s natural oxytocin release by stimulating the nipples with hand expression or pumping. Be aware though that nipple stimulation can cause particularly intense and prolonged contractions.

-

Evening primrose. Ellson says another option is to “place a capsule of evening primrose oil into the vagina to soften the cervix and encourage it to be more receptive to labor contractions.” This technique is somewhat controversial, though, and research has shown that it’s not necessarily effective. Some medical experts are fully against this option so be sure to check with your provider before moving forward with this method.

“Women having babies for the first time tend to have slower and later dilation of cervix,” Chuang says, adding that women who’ve previously given birth may have a dilated cervix as early as 37 weeks. But if you’re ever concerned about slow cervical dilation, don’t hesitate to reach out to your doctor.

If you’re approaching your due date (or are there already) and you don’t have a dilated cervix, the simple reality is that your body is just not in labor yet. Both Williams and Ellson say that no one really knows what specifically triggers the body to go into labor or why the cervix doesn’t always dilate completely. Chuang notes a posterior cervix, large fetal size or breech baby may be factors. It’s also possible your contractions just aren’t strong enough to pull the cervix open.

If things aren’t happening naturally, your doctor may want to induce labor. Depending on the situation, they’ll likely start out conservatively with physical interventions like a manual membrane sweep, which helps naturally release prostaglandins to soften the cervix, Chuang notes. Or, they may use a Foley catheter, which is essentially a balloon to help dilate the cervix. There are also different medications that can help induce labor and expedite cervical dilation to varying degrees, including Pitocin (the artificial form of oxytocin). If none of these options get the cervix to fully dilate, Williams says a c-section may be necessary.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take to dilate from 1 to 10 centimeters?

According to Chuang, the time frame for this can vary greatly, depending on baby’s position, how strong and frequent contractions are and whether it’s your first time giving birth. “On average, it may take around 6 to 12 hours for a first-time mom and less time for subsequent pregnancies,” she notes.

How dilated are you when you lose your mucus plug?

Unfortunately, there’s no definitive answer to this. While losing the mucus plug is a sign of upcoming labor, it doesn’t signify a specific level of cervix dilation, rather it “can happen at different stages of the labor process,” Chuang explains. In fact, you may even lose it before labor begins.

How painful is cervical dilation?

It’s no secret that childbirth hurts. “Cervical dilation can be a painful and intense process for many women,” Chuang says. But, again, this will be different for each person dependent on their pain tolerance and other individual factors. “Some women may experience mild discomfort, while others may experience more intense sensations,” she adds. Make sure you discuss ways to manage labor pains with your provider during pregnancy so you can feel prepared for the big day.

Remember, cervical dilation is an important part of the laboring process, but there are also other pieces that have to fall into place for the body to be ready for delivery. So whether you’re walking around with a 2 centimeters dilated cervix for a week or feeling discouraged because you aren’t dilated at all as your due date approaches, try to relax and trust that your body will get there (eventually) and baby will come—one way or another.

Please note: The Bump and the materials and information it contains are not intended to, and do not constitute, medical or other health advice or diagnosis and should not be used as such. You should always consult with a qualified physician or health professional about your specific circumstances.

Plus, more from The Bump:

Meleen Chuang, MD, is an ob-gyn and medical director of women’s health at the Family Health Centers at NYU Langone. She earned her medical degree from SUNY Stony Brook.

Denae Ellson, CNM, is a certified nurse midwife in Minnesota. She currently serves as an advanced practice nurse for Planned Parenthood. She earned her registered nursing degree from the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, and her master’s degree from Georgetown University.

Nicole Williams, MD, is an ob-gyn practicing in Chicago, Illinois. She earned her medical degree from Loyola University Chicago and completed her ob-gyn residency at Presence Saint Joseph Hospital in Chicago.

American Pregnancy Association, What is Dilation in Pregnancy?

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, What does it mean to lose your mucus plug?, October 2020

PeerJ, Physical activity during pregnancy and its influence on delivery time: a randomized clinical trial, February 2019

Cochrane Library, Sexual intercourse for cervical ripening and induction of labour, April 2001

Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Evening primrose oil and labour, is it effective? A randomised clinical trial, February 2018

Learn how we ensure the accuracy of our content through our editorial and medical review process.

Navigate forward to interact with the calendar and select a date. Press the question mark key to get the keyboard shortcuts for changing dates.